1. Introduction: The Mirage of Wealth(Big Bull India)

April 1992 was a strange time in India. The economy had just opened up, and optimism was in the air. But on Dalal Street, optimism had turned into hysteria. The Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) Sensitive Index (Sensex), which had languished around 1,000 points in 1991, had rocketed past 4,400 points in barely a year.

To understand the sheer magnitude of the 1992 scam, we cannot look at the stock market in isolation. We have to look at the psychological and economic state of India at that precise moment.

The Context: The “shackles” were coming off (1991-1992) Just one year prior, in 1991, India had faced its worst economic crisis. The country had almost run out of foreign exchange and had to airlift its gold reserves to London just to pay its bills. In response, the then Finance Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, presented the landmark 1991 Budget. He slashed import duties, devalued the rupee, and effectively killed the “License Raj.”

- Why this matters: For the first time in decades, Indians felt that the country was about to become an economic superpower. There was a genuine wave of euphoria. Harshad Mehta didn’t create this optimism; he hijacked it. He convinced the nation that the stock market was the engine that would drive this new India.

The Numbers: The 4X Explosion The paragraph mentions the Sensex jumping from 1,000 to 4,400. Let’s put that in perspective.

- A healthy stock market might grow 15% or 20% in a year.

- The Indian market grew 340% in roughly 12 months.

- The Valuation Gap: At the peak of this mania, the Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio of the Sensex was over 50. (For context, a P/E of 20 is considered normal). This meant people were paying ₹50 for every ₹1 of profit a company made. It was mathematically impossible for these companies to grow fast enough to justify those prices.

The Pied Piper: Harshad Mehta’s “Replacement Cost Theory” How did Mehta convince smart people to buy stocks at such insane prices? He used a pseudo-intellectual argument called the “Replacement Cost Theory.”

- He argued that old companies (like ACC Cement) should be valued not on their current profits, but on how much it would cost to build a new cement plant from scratch today. Since inflation had made building new plants expensive, he argued the old companies were undervalued.

- It sounded smart, but it was a lie designed to justify his manipulation. He famously drove the price of ACC Cement from ₹200 to ₹9,000.

The Cultural Impact: The “Lexus” Symbol The paragraph mentions an “imported Lexus.” This wasn’t just a car; it was a symbol. In 1992, you couldn’t just buy a foreign car in India; duties were astronomical. Harshad Mehta owned a Lexus LS 400, the only one in the country at the time.

- When he drove it to the BSE, brokers would cheer. He became the poster child for the “New India” where anyone could get rich. This image lured the middle class—doctors, teachers, and shopkeepers—to take their life savings out of safe banks and hand them over to brokers.

The “Rot” Beneath: The Systemic Hole The text says the run was built on a “systemic hole.” This is the crux of the scam. The money driving the Sensex up wasn’t coming from legitimate investors or corporate profits. It was coming from the banking system. Mehta was illegally siphoning liquidity from government bonds and pumping it into the stock market.

- Imagine using your credit card to gamble at a casino, winning, paying back the credit card before the bill arrives, and keeping the profit. That is what Mehta was doing—but with Crores of public money.

The Consequence: The April 23 Revelation When journalist Sucheta Dalal broke the story in The Times of India on April 23, 1992, the illusion shattered.

It revealed that the Indian financial system was primitive. It ran on “Trust and Paper Scraps”—specifically, the Bank Receipts (BRs) that Mehta had forged. There was no digital verification, no central depository, and no real oversight.

₹100,000 Crores Wiped Out: To understand this number, consider that in 1992, this amount was a significant percentage of India’s total GDP. The wealth didn’t just disappear; it transferred from the pockets of innocent retail investors (who bought at the top) to the debts left behind by the scam.

When the truth finally came out on April 23, 1992, it didn’t just crash the market; it wiped out ₹100,000 crores of market capitalization and revealed that India’s financial system was running on little more than trust and paper scraps.

2. The Mechanism: The “Ready Forward” Loophole

To understand how a single man could manipulate the entire Indian economy, we have to look under the hood of the banking system. The scam wasn’t about picking the right stocks; it was about exploiting a broken plumbing system in the Money Market.

A. The Constraint: Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) In the 1990s, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was very strict. It mandated that every bank must keep a significant portion (around 38.5% at the time) of its deposits in liquid assets, primarily Government Securities (G-Secs).

- The Pressure: If a bank fell short of this ratio on a Friday (reporting day), the RBI would impose heavy penalties. This created a desperate, weekly scramble for bonds.

- The Market: This trading of government bonds was huge—much larger than the stock market—but it was invisible to the public.

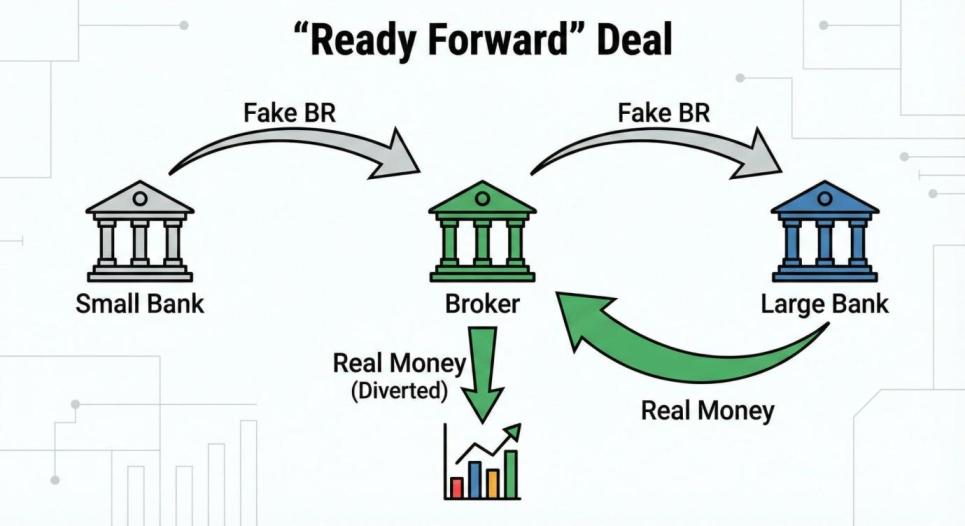

B. The Tool: The “Ready Forward” (RF) Deal Since banks only needed to maintain the ratio periodically, they didn’t always want to buy bonds permanently. They often just needed to borrow them for a few weeks to show the RBI inspectors.

- How it worked: Imagine Bank A has extra cash but needs bonds. Bank B has extra bonds but needs cash.

- The Deal: Bank B sells the bonds to Bank A today, with a signed agreement to buy them back in 15 days at a slightly higher price.

- The Analogy: It’s like a pawn shop. Bank B pawns its bonds to get cash, then reclaims them later with interest. This is a legitimate, legal financial instrument called a Repo (Repurchase Agreement) today. Back then, it was called a Ready Forward deal.

C. The Fatal Flaw: The Bank Receipt (BR) Here lies the root of the scam. The physical transfer of bond certificates in 1992 was a nightmare. It involved bundles of paper, manual ledger entries, and slow courier vans. To speed things up, banks invented a workaround: the Bank Receipt (BR).

- Instead of sending the actual bonds, the selling bank would give a piece of paper (BR) that effectively said: “I have sold you these bonds, but I am holding them in my vault on your behalf. Here is the receipt.”

- The Trust Factor: This system ran entirely on trust. Bank A accepted the BR because they trusted Bank B. There was no central digital registry (like NSDL today) to check if Bank B actually had the bonds.

D. The Heist: How Mehta Weaponized the BR Harshad Mehta realized that since no actual bonds were moving, he could just trade the receipts. And if he could trade receipts, he could trade fake receipts.

Here is the step-by-step mechanism of the fraud:

The Return: When the 15 days were up and the Ready Forward deal matured, Mehta would sell his stocks (at a profit), take the principal amount, and pay it back to SBI. SBI got their money back with interest and never knew the bonds never existed. Mehta kept the massive profit from the stock appreciation.

The Accomplice (Bank of Karad): Mehta colluded with small, obscure banks like the Bank of Karad (BoK) or the Metropolitan Co-operative Bank (MCB). These banks were willing to issue BRs even if they didn’t have a single bond in their vault.

The Victim (SBI / NHB): Mehta would approach a cash-rich giant like the State Bank of India (SBI). He would say, “I have government bonds for you to buy.”

The Exchange: Mehta would hand over a Fake BR issued by the Bank of Karad. SBI, trusting the banking system, would assume the Bank of Karad actually held the bonds.

The “Cheque Routing” Trick: This was the masterstroke. SBI would issue a cheque for the payment. Technically, this cheque should go to the Bank of Karad. However, Mehta managed to get the cheques credited into his own personal account.

Note: This was illegal. Account Payee cheques are never supposed to go to a broker. But through bribery and “sandwich transactions,” Mehta bypassed this rule.

The Pump: Suddenly, Mehta had ₹500 Crores of SBI’s money in his personal account for 15 days. He didn’t buy bonds. He pumped this money into the stock market (buying ACC, Apollo Tyres, etc.).

Instead of using that money to buy bonds, Mehta poured it into the stock market. He created a cycle of liquidity where he used bank money to pump up stock prices, booked the profits, and then (usually) returned the money to the banks before they noticed. It was a Ponzi scheme, but with bank funds.

3. The Mania: When Logic Left the Building

With thousands of crores of illegal bank money flowing into his accounts, Harshad Mehta became a whale in a pond. His buying power was so immense that he didn’t just predict the market; he was the market.

The “Replacement Cost” Fallacy To justify the insane prices he was paying for stocks, Mehta invented a narrative that captivated the nation: the Replacement Cost Theory.

- The Argument: He argued that a company like ACC (Associated Cement Companies) should not be valued based on its current earnings (which were modest). Instead, it should be valued on how much it would cost to build a new cement plant of that size today.

- The Flaw: This theory ignored a basic rule of investing: a company is only worth the cash it generates. But in the euphoria of 1992, no one cared about cash flow. They only cared about the price ticker.

The Case of ACC The most famous symbol of this mania was ACC Cement.

- The Rise: In late 1991, ACC was trading at ₹200. By April 1992, Mehta had driven it to ₹9,000.

- The Valuation: At this price, the company’s P/E ratio was astronomical. But retail investors, seeing the daily rise, felt that buying ACC was a “guaranteed” way to get rich. They sold land, jewelry, and even borrowed money at high interest rates to buy shares at the peak—shares that were being artificially propped up by stolen bank funds.

The “Tips” Culture During this period, the magazine Dalal Street Investment Journal became the bible for middle-class India. If a rumor floated that “Harshad bhai is buying this stock,” the price would hit the upper circuit within minutes. The fundamentals of the companies didn’t matter; only the “Big Bull’s” shadow did.

4. The Exposure: The Day the Music Stopped

Every Ponzi scheme has a breaking point: the moment when the money runs out. For Harshad Mehta, that moment came in April 1992.

The SBI Discrepancy The State Bank of India (SBI) was the giant of the banking world. Usually, their reconciliation (checking the books) was slow. But in April, the officials at the Public Debt Office (PDO) noticed a massive gap.

- The Missing Money: SBI’s books showed they had paid ₹500 Crores for government bonds.

- The Missing Bonds: Their vaults were empty. There were no bonds, and the Bank Receipts (BRs) they held were from small, insignificant banks that couldn’t possibly own that much debt.

Enter Sucheta Dalal While the bank officials were panicking internally, the information leaked to a young journalist at The Times of India, Sucheta Dalal. She had been hearing whispers about Mehta’s lavish lifestyle and the source of his funds.

On April 23, 1992, she published the article that changed Indian history. The headline didn’t scream “Scam”; it was technical, pointing out the reconciliation failure at SBI. But to those in the know, it was a death knell.

The Domino Effect Once the news broke, the banks stopped lending. The “cycle of liquidity” that Mehta relied on to keep stock prices high was cut off instantly.

- The Crash: Without fresh money to prop them up, share prices collapsed.

- The Panic: Banks rushed to cash in their Bank Receipts, only to find they were worthless pieces of paper. The chairman of Vijaya Bank, failing to cope with the shame of his bank’s involvement, tragically died by suicide, signaling the human cost of the fraud.

The “Big Bull” was grounded. The dream was over.

5. The Aftermath: From Chaos to Order

The Harshad Mehta Scam 1992 was not just a financial crime; it was an institutional earthquake. The sheer scale of the fraud—estimated at ₹5,000 Crores (approx. $3 billion adjusted for inflation)—paralyzed the country. Parliament was stalled, banking operations froze, and the Indian Stock Market Scam became global news.

But as the dust settled, the government realized that the “old ways” of the History of SEBI could not continue. The crisis became the catalyst for India’s most significant financial reforms.

A. The Janakiraman Committee The Reserve Bank of India immediately formed a committee under R. Janakiraman to investigate the depth of the rot. The reports were damning. They revealed that banks, brokers, and Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) were all complicit in a massive game of musical chairs with public money. The findings made it clear: self-regulation was a failure.

B. SEBI Gets its “Teeth” (The SEBI Act, 1992) Before 1992, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) existed only on paper. Established in 1988, it was a non-statutory body with no real power. It couldn’t fine anyone; it couldn’t arrest anyone. It was a watchdog that could bark but not bite.

On April 12, 1992 (ironically, just days before the scam broke), the government passed the SEBI Act, 1992.

- Statutory Power: This act gave SEBI legal authority. It could now summon individuals, conduct raids, suspend trading, and impose heavy penalties.

- The New Sheriff: In the years following the scam, SEBI aggressively used these powers to ban bad brokers and clean up the exchange. The Securities and Exchange Board of India history divides neatly into two eras: “Pre-1992” (weak) and “Post-1992” (powerful).

C. Breaking the BSE Monopoly: The Birth of NSE The government realized that the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) was essentially an “Old Boys’ Club.” The brokers protected each other, and the trading floor was opaque. To break this monopoly, the government did something radical: they built a competitor. In 1994, the National Stock Exchange (NSE) was launched.

- Screen-Based Trading: Unlike the BSE’s noisy “trading ring,” NSE was fully digital. It brought transparency that made it impossible to hide the kind of “fake receipts” Mehta had used.

- Dematerialization (Demat): The scam relied on physical paper receipts. To kill this risk forever, India moved to “Demat” accounts in 1996, converting physical share certificates into digital entries.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Big Bull

Harshad Mehta, The Big Bull India loved and then loathed, died in police custody in 2001. But his legacy is stamped on every trade made in India today.

Curious about where it all began? While Harshad Mehta was the modern “Big Bull,” he wasn’t the first. The Indian market actually started with just five men under a Banyan tree in the 1850s, led by the original “Cotton King,” Premchand Roychand. Before the digital age and complex banking scams, the market ran entirely on verbal promises and “Cotton Mania.” Read the prequel to this story here: [The “Banyan Tree” Beginnings: How the BSE Was Born]

The Harshad Mehta Scam 1992 was a painful tuition fee that India paid to learn modern economics. It destroyed the lives of thousands of investors, but it also forced the creation of a robust, digital, and regulated market. Today, when you buy a stock on your phone in seconds with complete safety, you are enjoying the benefits of the walls built to stop another Harshad Mehta.