The History of the indian Stock Market : Imagine walking down Dalal Street today. You are surrounded by skyscrapers, the hum of servers processing millions of trades per microsecond, and the iconic Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers standing as a fortress of Indian wealth. It is organized, digital, and heavily regulated.

1 – Introduction

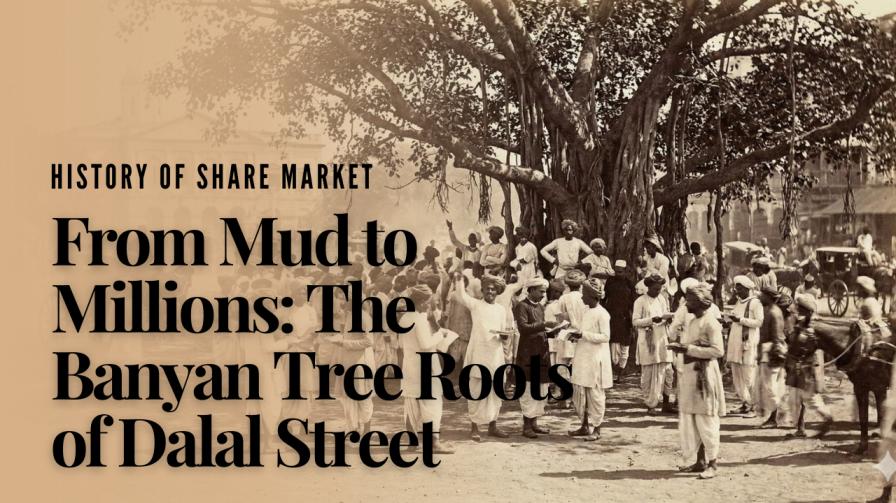

Now, rewind the clock 170 years. Erase the towers. Silence the servers. Instead, picture a dusty, humid afternoon in front of the Town Hall in South Bombay. There are no computers, no trading rings, and no buildings. There is just a sprawling Banyan tree, providing shade to a small group of five men.

They aren’t shouting or typing; they are whispering rates and making deals with nothing but a handshake.

This humble gathering in the 1850s wasn’t just a meeting of friends; it was the embryonic heartbeat of what would become the oldest stock exchange in Asia. The story of the Indian share market doesn’t begin with a ribbon-cutting ceremony—it begins with resilience, chaos, and a few brokers moving from tree to tree to keep their trade alive.

2. The Setting: Bombay in the 1850s – A City in Transition

To understand the birth of the stock market, we have to look at the Bombay (now Mumbai) of the mid-19th century. It wasn’t yet the financial capital of India, but it was waking up. The British East India Company was losing its grip, and trade was opening up.

Railways were being laid, the telegraph was connecting cities, and the port was buzzing. In this atmosphere of rapid modernization, bank shares became the first “hot” commodity. Commercial banks were springing up, and for the first time, wealthy merchants realized that money could make more money without them physically moving goods.

But there was a problem. There was no designated place to trade these shares. So, the brokers went to where the space was—the Banyan tree near the Town Hall. It was informal, loud, and completely unregulated. If you made a deal, you honored it. If you lost money, you absorbed it. It was a gentleman’s game played on a dusty street corner.

To understand the birth of the stock market, we must look beyond the romance of the Banyan tree and understand the economic revolution happening in Bombay. The 1850s wasn’t just another decade; it was the specific moment when Bombay evolved from a medieval trading post into a modern financial hub.

1. The Legal Catalyst: The Companies Act of 1850 Before the 1850s, forming a company with “tradable shares” was legally difficult. The game-changer was the Companies Act of 1850. This legislation, modeled after English law, introduced the concept of “limited liability” to India.

- Why this matters: Suddenly, you didn’t need to be a solitary merchant risking your entire family fortune. You could pool money, issue shares, and build a “Joint Stock Company.” This created the supply of shares that the brokers under the tree would eventually trade.

2. The Infrastructure Boom: The Train that Changed Everything On April 16, 1853, history was made. The first passenger train in India ran from Bori Bunder (Bombay) to Thane. *

Getty Images

- The Economic Impact: The Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR) didn’t just carry passengers; it connected the cotton-growing hinterlands of the Deccan directly to Bombay’s port. This made Bombay the undisputed “Gateway of India” for trade, surpassing Calcutta in commercial importance.

3. The “Hot” Commodity: Bank Shares With trade booming, merchants needed credit. This led to the rise of commercial banks.

- The Bank of Bombay (est. 1840): This was the premier stock. Its shares were the “blue chips” of the 1850s.

- Other Players: The Oriental Bank, the Agra Bank, and the Chartered Mercantile Bank soon followed.

- For the first time, wealthy Parsi and Gujarati merchants realized they could make money by trading the ownership of these banks rather than just depositing money in them.

4. The Culture of “Zuban” (Word of Honor) The trading under the Banyan tree (specifically in front of the Town Hall at Horniman Circle) was unique because of its participants.

- The Crowd: It was dominated by Parsis and Gujaratis (Banias).

- The System: There were no written contracts, no lawyers, and no regulatory body like SEBI. The entire market ran on “Zuban”—the verbal promise. A nod of the head or a specific hand signal was as binding as a legal document. In a chaotic street corner with no walls, reputation was the only currency that mattered. If a broker reneged on a deal, he was exiled from the community instantly.

This unique mix of new laws (1850 Act), new tech (Railways/Telegraph), and old-world ethics (Zuban) created the perfect breeding ground for the Indian capital market.

3. The Catalyst: The American Civil War & Cotton Mania

If the Banyan tree provided the place, the American Civil War provided the money.

In 1861, war broke out in the United States. This might seem irrelevant to Indian History of Bombay Stock Exchange, but it was the spark that lit the fire on Dalal Street. America was the world’s supplier of cotton to the textile mills of England. When the war blocked American ports, England became desperate for cotton. They turned to the only other viable source: India.

Almost overnight, the price of Indian cotton skyrocketed. Money poured into Bombay like a tidal wave. Merchants who were once modest traders became millionaires in weeks. This period, known as “Cotton Mania” or “Share Mania,” flooded the city with excess liquidity.

With so much cash floating around and nowhere to put it, people turned to speculation. They bought shares in anything—shipping companies, reclamation projects, and banks. The group under the Banyan tree grew larger, louder, and wealthier. The market wasn’t just a hobby anymore; it was an obsession.

4. The Protagonist: The First “Big Bull”

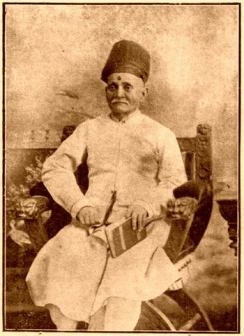

At the center of this storm was one man: Premchand Roychand.

Long before Harshad Mehta or Ketan Parekh, there was Premchand. He was known as the “Cotton King” and the “Big Bull.” He wasn’t just a participant in the market; for a few years, he was the market.

Premchand was a man of immense foresight. He understood that for Bombay to be a global city, it needed infrastructure. He used his massive profits to fund reclamations in South Bombay and even donated the money to build the famous Rajabai Clock Tower at the University of Mumbai (named after his mother).

But in the trading ring (or rather, under the tree), he was aggressive. He had an unparalleled ability to gauge risk and control liquidity. Brokers would watch his every move. If Premchand was buying, everyone bought. If he sold, panic set in.

5. The Crisis: When the Bubble Burst in History of Indian Stock Market (1865)

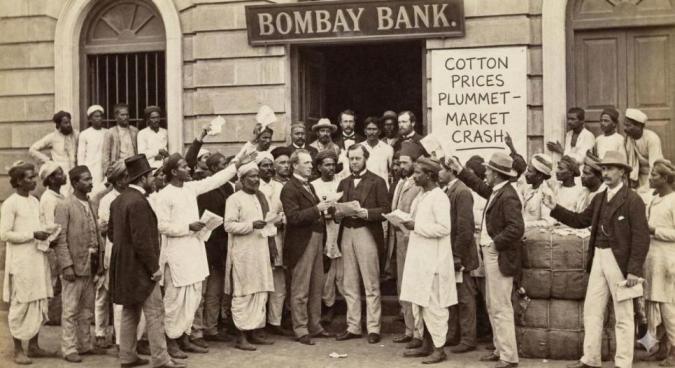

Every bubble must burst, and the “Cotton Mania” was no exception. In 1865, the American Civil War ended.

Almost instantly, American cotton flooded the global market again. The demand for Indian cotton plummeted. The prices that had reached the stratosphere came crashing down to earth.

The devastation was total. The “time share” companies and banks that had sprung up overnight went bankrupt. Wealth that had been built on paper evaporated in days. The chaotic, unregulated nature of the market meant there was no safety net. Even the mighty Premchand Roychand faced severe losses, though he eventually rebuilt his fortune.

To understand the crash, you have to understand the height of the madness. By early 1865, Bombay was in a state of delirium. The shares of a company called Back Bay Reclamation, with a face value of ₹5,000, were trading at an insane ₹50,000. The Bank of Bombay’s shares had surged from ₹500 to nearly ₹2,850. Servants, clerks, and shopkeepers had quit their jobs to become full-time speculators.

Then came the telegram that froze the city.

In April 1865, the American Civil War ended. The Confederate states surrendered. Almost instantly, the American ports reopened, and superior American cotton flooded the Liverpool market. The British mills, which had been paying exorbitant prices for Indian cotton out of desperation, immediately switched back to the American supply.

The Price Collapse The price of Indian cotton didn’t just dip; it collapsed. In Bombay, panic set in. The “Time Bargains” (an early form of futures contracts) that traders had signed were set to mature on July 1, 1865. Everyone knew that when that date arrived, they would have to pay the difference in price—but no one had the cash.

July 1, 1865: “Black Day” When the settlement day arrived, the default was almost universal.

- The Bank of Bombay, which had recklessly lent money to speculators (often on the advice of Premchand Roychand), found its coffers empty. It eventually lost its charter—a humiliation for a “Presidency Bank.”

- Wealth Evaporated: Giant merchant families who had been the pillars of Bombay society declared bankruptcy overnight.

- Exodus: The economic ruin was so severe that it is estimated 21% of Bombay’s population left the city in the years following the crash, returning to their villages because there was no work and no money left.

The Fall of the Big Bull Even Premchand Roychand was not spared. He had a debt of over ₹42 lakhs (a staggering sum in 1865). However, unlike many others who fled or hid, Premchand stayed. He liquidated his assets, sold his properties, and eventually paid back nearly every rupee he owed.

This crash was the “Great Depression” of 19th-century India. It taught the city a painful lesson: a market without rules is just a gambling den. It was this very disaster that convinced the brokers they needed to form an association—a move that would eventually lead to the creation of the BSE.

6. Conclusion: From Roots to Roof

The crash of 1865 was a painful lesson, but it was a necessary one. The brokers realized that they couldn’t continue trading on street corners with verbal agreements. They needed order, rules, and a roof over their heads.

It took a decade to recover, but in 1875, that same group of brokers who had started under the Banyan tree formally established the “Native Share and Stock Brokers Association.”

We’ve spent the last hour talking about the madness of the Cotton Mania and the devastation of the 1865 crash. You might look at that crash and think, ‘What a disaster.’ But as historians, we have to look at it differently. We have to ask: What did the disaster build?

And that brings us to our conclusion: ‘From Roots to Roof.’

Think of the 1865 crash as the growing pains of a teenager. Before the crash, the Bombay market was like the Wild West—wild, informal, and dangerous. After the crash, the brokers realized they couldn’t operate on chaos anymore. They had learned a hard lesson: Trust is good, but institutions are better.

So, look at what happens next. It takes them ten years to lick their wounds—a ‘lost decade,’ if you will. But in 1875, the survivors of that crash come together. They don’t just meet under the tree; they form a legal body. They call it the ‘Native Share and Stock Brokers Association.’

Now, pay attention to that name. ‘Native.’ In British India, this was a proud assertion. This wasn’t a club run by the British colonial masters; this was an Indian institution, run by Indian merchants, for the Indian economy.

They drafted a Constitution. Why is that important? Because suddenly, you have rules.

- Entrance Fees: You can’t just walk in off the street anymore; you have to have skin in the game.

- Code of Conduct: If you cheat, you’re out.

- Dispute Resolution: If we disagree on a price, we don’t fight; we follow the process.

This moment in 1875 is the transition from an ‘informal gathering’ to a ‘formal institution.’ It is the moment the Banyan tree metaphorically turns into a building.

Fast forward to today. When you open your trading app—whether it’s Zerodha or Groww—and you see those numbers flashing red and green, you are participating in a system that was designed by those men in 1875. The technology has changed completely. We’ve gone from shouting under a tree to high-frequency trading algorithms.

But—and this is the key takeaway for today—the spirit hasn’t changed. The ambition to create wealth, the resilience to survive a crash, and yes, that terrifying volatility… that is the DNA of the Indian market. It was there under the tree, and it’s there in your smartphone.

So, when you see the Sensex go up or down, remember: You are looking at the modern leaves of a very, very old tree-BSE history .

This association would eventually draft a constitution, set entrance fees, and enforce a code of conduct. Over time, it grew, modernized, and built the iconic towers we see today.

So, the next time you place a trade on your phone, remember the Banyan tree. The technology has changed, but the spirit of the Indian market—ambitious, resilient, and occasionally volatile—remains exactly the same.

The 1992 Scam: When the Big Bull Broke the Bank Harshad Mehta drove the Sensex from 1,000 to 4,400 points in a year, but his empire was built on a massive banking loophole called “Bank Receipts.” He siphoned over ₹5,000 Crores from banks like SBI to artificially pump up stock prices, driving companies like ACC from ₹200 to ₹9,000. When the bubble burst, it wiped out ₹100,000 Crores of wealth overnight and revealed a financial system running on little more than blind trust. Read the full story of how this scam changed Indian finance forever and forced the birth of SEBI